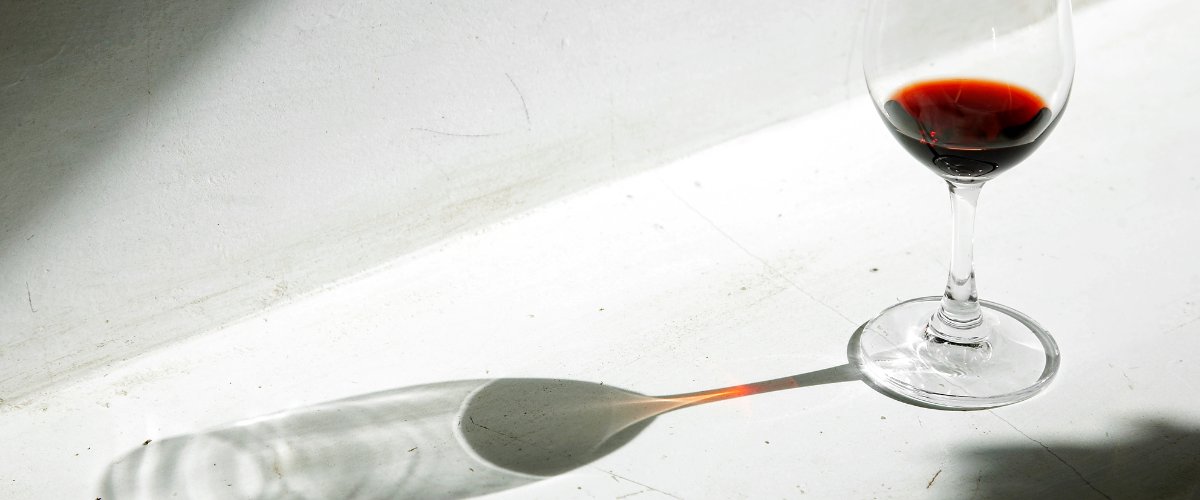

What Makes Red Wine… Red?

Well, this is awkward…

By Erin Henderson

I’ve been a sommelier since 2008. I opened The Wine Sisters in 2012. I began teaching wine classes at George Brown College in 2015. And I started my own Wine School in 2018.

Despite having hosted innumerable wine tastings and led countless wine classes, sometimes I can’t see the bottle for the glass.

You may also like: Why Are Red Wines Served Warm?

This is why I love teaching beginner’s wine workshops. The questions I get are so earnestly… well, beginner, that I have to check myself before racing ahead.

At the start of our foundational sessions, we go through the high-level basics of making wine. And as we discuss the general overview of making red wine, most students are shocked to find out nearly all red wine grapes have clear insides. Therefore, when squeezed, the juice that comes out is also clear. (So yes, it’s possible to make a white wine from red grapes – this happens in Champagne all the time.)

So… how does a red wine become red?

There are a few ways to get the colour into clear juice, but the best method to understand is the likely the most common. Called maceration, red grape skins are left with the clear juice to gain colour (and texture, more on that in a minute.) A few minutes or hours will achieve some sort of shade of pink; a few hours or days will achieve some sort of colour of purple.

You may also like: What's the Difference Between Acid and Tannin?

Grape skins don’t just add colour, they also add some healthy compounds like resveratrol and polyphenols, which is why health advocates and Blue Zone devotees advise drinking rich red wines for longevity. But grape skins (and seeds and stems) also contain something called tannins, bitter-tasting molecules with an astringent texture that can range from barely perceptible to strongly grippy – like you just left the dentist with a mouth full on cotton balls.

The colour of the wine can hint at how tannic the wine will be: deeper coloured wines tend to have stronger tannins, lighter wines usually have smoother, or even no, tannin. Of course, like all things related to wine this isn’t a hard and fast rule: grape variety, ripeness levels, and wine making techniques all contribute to a wine’s final structure.

Some grapes, like Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah, have thicker skins, so are generally more pigmented and often have firmer tannin. Other grapes, like Pinot Noir or Gamay, have thinner skins and are often more translucent and lighter in tannin.

Your Next Read: The Four Ways to Make Rosé